At the International Cities and Town Centre Conference 2018 in Perth, Australia, Nick Booth of nbd space delivered a presentation based on his award winning original research on the importance and use of Odors within the built environment to help build a sense of place and build memories of spaces. The above film is the audio of his presentation along with his slideshow.

An Examination of the Olfactory Experience and its Use in Urban Design.

Nick Booth MA (Urban Design)

Abstract

The urban form is often viewed as a series of spaces through which we travel, navigating ourselves by way of cognitive spatial recognition, using exterior markers and our own inner construct of the world. It is suggested that odours have the ability to affect our behavioural and cognitive process and form markers that aid in the construction of a spatially organized world.

Building in the Olfactory Experience is an examination by survey within a selection of urban forms of the degree, extent and level of detail with which we perceive odours and the degree to which they provide added meaning or contextualisation to spaces. It broadens current knowledge by providing an odour survey format and suggesting how odour can be manipulated by adopting recognised urban design techniques.

Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: The Problem

- Chapter 2: The Olfactory Experience

- Chapter 3: Enquiry by Survey

- Chapter 4: The Odour Surveys

- Chapter 5: Analysis and Application

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Bibliography

Preface

“He stopped dead in his tracks, his nose searching the hither and thither in its efforts to recapture the fine filament, the telegraphic current that has so moved him. A moment, and he had caught it again: and with it this time came recollection in fullest flood. Home!”The Wind in the Willows – Kenneth Grahame

It has always occurred to me that the modern experience of place is far removed from that experienced by past generations. Ancient monuments as we see them today are merely the bare bones of what they used to be. Banished are the heady but often unpleasant odours of life and death that used to form a vital component of the everyday and familiar. In so doing, have we surrendered ourselves to a barren and sterile olfactory experience and simply thrown the baby out with the bath water?

One of the principal aims of urban design is to create or mould townscapes that produce ‘a sense of place’. To create an environment that both stimulates and provides assurance. An essential dimension is an awareness and appreciation of how the spaces around us are perceived and experienced, for in order to be affected by an environment, we must perceive it. Predominantly, emphasis has in the past been placed on the visual with more recent work examining the use of symbolism and meaning. However, it is increasingly recognized that perception of place is more than simply defined by its physical construct. In order to fully comprehend the nature of a place, the place must be a place ‘sensed’. It should seek to have ‘depth’, to satisfy or at least register with as many of the ways that a human can be aware and recognise their surroundings, be it through the senses of sight, sound, smell, touch and perception of heat for example. Only then may a spatial-sensory picture be constructed on several levels, thus allowing for the user to both engage with and recognize something of themselves or their perception of who they are reflected back to them from their surroundings. As Gaston Bachelard reflects, once a place has been grasped and taken into the human imagination, it can never again be remembered just by physical measurement alone. Importantly, when done so, it also can no longer be treated with a sense of indifference.

It is recognized that memories of prior personal and cultural experiences play an important role in forming the background to how the human mind perceives and reacts to its surroundings. Often it may be something hidden from view or not immediately obvious within the various strands of a place that can trigger a memory or affect ones subconscious reaction to it. There is a growing body of work that suggests that the most persuasive motivational factor in human behaviour is odour. Research by S. Van Toller, J R King, and most recently through the work of Nobel Prize for Medicine winners Richard Axel and Linda Buck, suggests that odour is capable of producing profound reactions in the mood and memory centres of the brain. It has been suggested that this is due to the close proximity and high level of integration between the limbic system, being the area of the brain that controls emotions and mood states, and the olfactory pathways. Intimate and immediate emotions can be produced through smells ability to evoke memories. Further, it has also been suggested that olfaction is linked far closer to the primal, older parts of the human brain than both the visual or audio senses. Smells therefore are capable of creating a reaction that is instinctive and free from rationalization. Take, for example, the smell of seaweed. This possesses the ability to not only conjure immediate memories of childhood holidays, such as rock pools, Cornish harbours and so on, but also evokes a powerful sense of the oceans depth at a primeval level that goes beyond simple recollection of memories. Therefore, smells are not only a powerful vehicle for memory, but also are capable of reaching deep into the sub-conscious to the primitive. They have the ability to allow us to experience a place at a local level, but connect to it with the core of ourselves.

It would therefore appear that there is a clear link between our olfactory sense and our ability to make spatial judgements and connections to a place, albeit through association. Despite this link however, there appears to have been only limited research into how our urban environment can be manipulated to appeal to our olfactory cues.

It is acknowledged that the need to build an urban environment that addresses and delights in all of the possible sensory recognitions has been recognized amongst leading theorists for some time. In his books, “The Image of the City” (1959) and “Managing the sense of a Region” (1976), Kevin Lynch has made initial studies of the sensory experience of the city, drawing the conclusion that to ignore our non-visual senses is to produce a sterile urban environment. He writes ‘Smells is a suppressed issue. It is rarely discussed except when some noxious odour is pejorative (“this place smells”). Yet smell is an intimate part of the character of a locale…smells evoke memories; they can be delightful or abhorrent’ (Lynch, 1976, pg103). Ian Bently also recognized the ability of smells to bring richness to a place within his manual for designers ‘Responsive Environments’.

Recent work has also been undertaken within the architectural community, most noticeably within the works of Juhani Pallasmaa (The Eyes of the Skin 2005), J.M. Malner and Frank Vodvarka (Sensory Design 2004) and A Barbara and Anthony Perliss (Invisible Architecture 2006). It is also noted that the possible positive impact of fragrances have not been overlooked by the private sector, most noticeably within theUnited StatesandJapan. Shopping Centres and several large companies freely acknowledge that they employee air circulation and heating systems with fragrances such as lemon and cedar with the direct intention of increasing alertness, reducing stress or enhancing a positive sense of well being. However, despite the above, little has been produced with the specific aim of providing a working manual for urban designers working within the public realm to utilize the olfactory dimension.

To explain why, it is legitimate to say that in part, this can be blamed on cultural perspectives. Unlike many eastern and South American cultures, in the west, as far back as the ancient Greek Philosophers, the very emotive nature of the sense of smell has been seen as being an unwelcome and destructive remnant of our more primitive past. The traditions set by Plato and Kant viewed human rationality as the meaningful way forward, thus distrusting emotions and aligning particular contempt for smell. Laws, planning and architecture, as the built expression of the art of society, have all tried to remove us, both perceptually and physically from any possible offensive smells from our day to day experience. The result is that smells no longer play a role in our urban life and we have become untrained in the art of olfactory.

On a more practical level, it must also be appreciated that in attempting to describe or create a working guide for an urban designer to follow, appraisals will be different from the visual appraisals that most are more familiar with. Odours are by definition, the invisible dimension. Then the sheer complexity of the relationship between space and odour is daunting. The task of attempting to describe and represent in pictorial form the huge variances of odour is magnified by the multiple levels, or ‘notes’ in which odours reveal themselves to us, much like the aftertaste of wine. Without the trained nose of a perfumery, the ability to identify and transcribe odours presents all manner of difficulties. Our reaction to them can be influenced by their persistence, timing, saturation, as well as the particulars of the spaces in which it is experienced, such as its size, dimensions, how air moves through it, what activities occur within it, and from what it is formed. J. Douglas Porteous points out that “any conceptualization of smellscape must recognize that the perceived smellscape will be non-continuous, fragmentary in space and episodic in time, and limited by the height of our noses from the ground, where smells tend to linger.” (Porteous, 1990, pg25). Lastly, it is also important to remember that the emotive and personalized nature of olfactory may result in often widely different reactions from different people and cultures to the same odour. However, it would appear that valuable sensory experiences are currently being ignored or at best sidelined, and that this hidden dimension may hold unexplored links to how we might not only increase the richness of the urban environment, but also regain some emotional connection with nature and our own core self. It is therefore considered that the investigation and creation of a working guide of the olfactory dimension would provide a valuable addition to the material available to urban designers.

Aims

It was therefore the intention to create a working manual for the recording of odours, their strength, positive or negative associations and their possible impact upon perception through association. It is hoped that through such a manual and the associated understanding how certain key elements can work within the environment, that the olfactory dimension can be utilized as a working tool in urban design to increase the richness of experience.

Chapter 1: The Problem

1.1 Introduction

Writing in “Space and Place, The perspective of Experience”, Yi-Fu Tuan speculates “Odors (sic) lend character to objects and places, making them distinctive, easier to identify and remember. Odors are important to human beings. We have even spoken of an olfactory world, but can fragrances and scents constitute a world? “World suggests spatial structure; an olfactory world would be one where odors are spatially disposed, not simply one in which they appear in random succession or as inchoate mixtures. Can senses other than sight and touch provide a spatially organized world?” (Tuan Y, 1977: 11).

One of the principal aims of urban design is to create or mould urban forms that produce a sense of place. To create an environment that both stimulates and provides assurance. An essential dimension is an awareness and appreciation of how the spaces around us are perceived and experienced, for in order to be affected by an environment, we must perceive it. Predominantly, emphasis has in the past been placed on the visual with more recent work examining the use of symbolism and meaning. However, it would appear that perception of place is more than simply defined by its physical construct. In order to fully comprehend the nature of a place, the place must be a place ‘sensed’. Yet, our potentially most evocative sense, that of olfactory, is largely ignored or overlooked in the design process other than to remove unpleasant odours.

The intention is therefore to examine whether the olfactory sense can provide a spatially organized world? Thus –

a) To examine the reasons behind the apparent under utilisation of the olfactory experience as a place making tool within Urban Design.

b) To gain a working knowledge of the role odours play in human perception and its possible ability to shape cognitive and mental mapping process.

c) To survey selected townscapes to broaden the knowledge as to the extent of odour perception and those features that promote perception utilising an odour classification system based on research and aimed at odours produced within the built environment.

d) To extrapolate the information gathered to suggest simple practical design guidelines formulated around existing ocular centred techniques in order to utilise the olfactory experience as an aid to contextualisation.

1.2 Methodology.

The process will begin through a contextual survey of the existing books, studies and any other literature relating to the first two stated objectives. It would appear at first that unlike the identification and copying of visual patterns to strengthen the legibility of the urban form, the often cited emotive and mnemonic abilities of odours are largely disregarded by urban design and planning professionals. Therefore, the review will concentrate on an examination of general texts relating to urban design, architectural and behavioural science focusing on existing urban design techniques; cognitive and mental mapping processes; the philosophical perception of odours within western thinking; the measuring and recording of perception and spatial dimensions of places to identify how both visual and non-visual elements are interpreted, recorded and then analysed; studies on the recognition and preferences of odours; and existing literature relating to expanding sensory design. It is intended that by doing so, a greater understanding will be reached of how odours are perceived; the current assumptions as to their limitations in contributing to legibility and character, both culturally and within an ocular centric design framework and what current literature exists that seeks to expand the use of sensory design.

The next stage will be to establish the extent to which these assumptions of the olfactory experience are correct. It is considered that this is best tested through the technique of survey, based on existing research and channelled in part along similar lines of investigation as those used to identify visual patterns in order to examine potential commonality. The surveys will therefore consist of a series of walks through selected townscapes by test subjects concentrating solely on the olfactory experience and measuring the extent, detail and emotional responses of the test subjects to odour perceptions and its impact on their contextualisation of the spaces. It is likely that initial analysis of results will identify errors within the survey technique. Identifying and then repeating the process should allow for corrections to be undertaken and anomalies to be noted.

The last stage will be to analysis the results produced to establish through extrapolation what level and intricacy of odour perception occurs, what physical forms within the urban townscape potentially amplify or diminish odour perception and how these forms might follow established visual patterns so as to suggest how potential commonality might provide a simple guide as to utilising the olfactory experience as a design tool.

Chapter 2: The Olfactory Experience

2.1 Urban Design Traditions

It can be suggested that the intended aims and process of urban design derive from three, often interlinked schools of thought (Carmona M et al, 2003).

The first, described as the ‘visual-artistic’ tradition views the process as a natural continuation of architecture, in which the aesthetics and visual qualities of places are to be examined, identified and reproduced. Typified by the work of Gordon Cullen who coined the phrase “Townscape”, it takes a purely ocular centric approach, viewing all the elements of the urban form and their manipulation by design as an act of staging, stating that “a city is a dramatic event in the environment” (Cullen, 1971: 8).

The second is described as the ‘social usage’ tradition. Deriving from the work of Kevin Lynch and his book “The Image of the City”, it shifts the emphasis towards perception of place, examining the links between spaces and the activities associated with them, and by so doing, enhancing the rich diversity of urban interconnectivity.

The third, and most recent, can be viewed as a politicised blend of both earlier views, described as the ‘making places’ tradition. Typified by the works of Allan Jacobs and the ‘Responsive Environments’ group of the then Oxford Polytechnic, this views urban design as the process by which inclusiveness, choice, vibrancy and aesthetic quality are produced in order to compliment and stimulate the behavioural responses of the user (Carmona M et al, 2003).

2.2 Behavioural Response and Attaching Meaning

With all three traditions, much emphasis is placed on the urban experience as partly being the moving through a sequence of spaces, recognising and understanding each by way of our own cultural perception of its character, and by so doing gaining a sense of connectivity and ownership with our surroundings. Cullen describes this as a “sympathy with the environment” (Cullen, 1971: 10), Kevin Lynch as “Sense, the degree to which places can be clearly perceived and structured in time and space” (Carmona M et al, 2003), Jacobs as ‘Identity’, ‘Authenticity’ and ‘Meaning’ (Carmona M et al, 2003), and by the Responsive Environment group as ‘Legibility’, or “the quality which makes a place graspable” (Bently I, 1985, 42).

It is suggested that perception, or sense of place, is a behavioural response derived in part from our own cultural background and past experiences recalled through spatial cognitive learning and mental mapping based primarily on physical forms. Or put simply, mental mapping is “the encoded structure in our long-term memory of what is where” (Soini, 2001: 227). Downs and Stea suggest that cognitive mapping is selective and is based on criteria’s of functional importance and distinctiveness or imageability (Downs et al, 1977). Whilst functional importance is unlikely, it can perhaps be suggested that within a monotonous area, places that constantly exude certain odours may become associated and thereby recognisable by the odour. By being distinctive it thus becomes a contributing factor in the mental mapping process. This does however suggest that the environment is an object that people stand outside of, and are essentially passive unless triggered by stimuli either external or internal.

2.3 Sensory and Emotive Response

Exponents of humanistic geography, such as Agnew and Relph, take an alternative view, suggesting that rather than standing outside of our surroundings, the environment is actually a personalised internal construct based on our own subjective sensory experience of place and our emotional responses to it (Soini, 2001). We experience our surroundings, its components and patterns through our own sensory perception, filtered through culture and memory and by doing are able to form an emotional attachment to it. Through this, a far deeper spatio-sensory picture is constructed across several levels, thus allowing for the user to engage with and recognize something of themselves, or their own mental construct of who they are, within their surroundings. In so doing so, they create an indelible connection with the space.

In their book “Sensory Design”, J M Malnar and F Vodvarka, refer to the works of Gaston Bachelard who describes such places as “eulogized space” and write “space that has been so seized upon by the human imagination can never remain indifferent space subject to physical measurement alone” (Malnar J et al, 2004: 3). They go on to examine the work of Malcolm Quantrill who suggested that this in part is formed by our recognition of types in the built form, or ‘universal motifs’, symbols that carry meaning and which when arranged in different patterns form the specific qualities of each space (Malnar J et al, 2004). It can be suggested that these qualities do not solely reside within the physical aspects of space and that sensory response to these ‘motifs’ are not derived by visual clues alone. Individual character can be derived from sounds, odours, activity and so on. Indeed, Piet Vroon has stated that odours can act as a memory aid and imbue a specific place with meaning based on experiences and events of the past (Malnar J et al, 2004). As such, it is considered that testing to see if odours are indeed capable of performing the role of type or motif, primarily through its ability to trigger emotions and memories is a central component of this study.

2.4 Odours Initial Recognition

It was acknowledged by Urban Designers such as Lynch as far back as the late 1950’s of the need to build an urban environment that addresses and delights in all of the possible sensory recognitions. In his books, “The Image of the City” (1959) and “Managing the sense of a Region” (1976), Kevin Lynch has made initial studies of the sensory experience of the city, drawing the conclusion that to ignore our non-visual senses is to produce a sterile urban environment. He acknowledges that odour in particular is capable of producing a strong emotional and mnemonic response. He writes ‘Smells is a suppressed issue. It is rarely discussed except when some noxious odour is pejorative (“this place smells”). Yet smell is an intimate part of the character of a locale…smells evoke memories; they can be delightful or abhorrent’ (Lynch, 1976: 103). Similarly, the Responsive Environments group also recognized the ability of smells to bring richness to a place within their manual for designers, and recent work relating to sensory design has also been undertaken within the architectural community, most noticeably within the works of Juhani Pallasmaa (The Eyes of the Skin, 2005), J.M. Malner and Frank Vodvarka (Sensory Design, 2004) and A Barbara and Anthony Perliss (Invisible Architecture, 2006).

2.5 The mistrusted sense in a visual-centric world

Despite the suggestions made by previous commentators as to the abilities of odours at both behavioural and humanistic level, there appears reluctance to exam how the olfactory experience can be actively utilised within urban design. The following sections examine the background to some of the factors that have led to the traditional mistrust of odour and the numerous variances that occur both within the physical world and the internal process of perception that go some way to explain why odours are difficult to control or even survey with any reasonable degree of continuity.

2.6 Western philosophical and Scientific Rejection.

In his book “Odori”, Gianni De Martino states “the sense of smell has been considered a primitive, animal, instinctual, voluptuous, erotic, egotistic, impertinent, libertine, frivolous, and asocial sense, one that goes against our free will (since it forces us willy-nilly to confront unpleasant sensations) and is incapable of getting beyond the primal solipsism of subjectivity.” (Reproduced by Barbara A et al, 2004:140). Unlike many Eastern and South American cultures, as far back as the ancient Greek Philosophers the very emotive nature of the sense of smell was viewed in the west as being an unwelcome and destructive element that obstructed ‘rationality’ and the belief that absolute truth must lie outside of sensations. Anthony Synnott writes in his article “Puzzling over the Senses: From Plato to Marx”, “the Greek tradition insisted on drawing a clear distinction between the senses and the mind, and on the epistemological and metaphysical superiority of the latter. The senses had their place, but that place was low.” (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004: 11).

That is not to say however that the Greek Philosophers dismissed all senses as Pallasmaa comments in “The Eyes of the Skin”, the works of Plato and Aristotle placed vision as “the noblest of the senses” (Pallasmaa J, 2005: 15) and the principal basis for understanding. It was suggested that vision allows us to frame images, to pick out detail or focus upon variety, and in doing so, allows us to make intellectual responses to what we perceive. It is interesting to note that the root of the word “idea” is the Greek idein, meaning ‘to see’. Malnar and Vodvarka note that “philosophical writings of all times have abounded with ocular metaphors to the point that knowledge has become analogous with clear vision and light as the metaphor for truth.” (Malnar J et al, 2004: 15).

It was however during the period of the Renaissance that vision became the unchallenged sense of reason. The invention of geometric perspective and the movable type of the printing presses placed the eye at the centre of our perceptual understanding of the world. The development and sub-division of the sciences from wisdom, and its demand to create type and classification placed the emphasis on the intellect and the measurable. As Pallasmaa comments, “The gradually growing hegemony of the eyes seems to be parallel with the development of Western ego-consciousness and the gradually increasing separation of the self and the world.” (Pallasmaa J, 2005: 25). Some commentators suggest that by the end of the Great War, the modern movement sought a form of design framework free of the constraints and ‘stain’ of human nature, the failings of which they viewed as having led to the conflict (Malnar & Vodvarka, 2004).

Research, including that reported by Piet Vroon in “Smell: The Secret Seducer” has shown the ability to recognise odour is undertaken by the evolutionally older parts of the brain, such as the brain stem, the pituitary gland and the limbic system. It is noted by Vroon that it is these parts of the brain that are also connected with our ability to have feelings, motivation and emotions. We therefore have an emotional reaction to an odour before we translate it into cerebral judgement and thus onto conscious behaviour. It is suggested that this ‘primitive’ part of the brain is associated with our survival instinct and that our emotional faculties have the ability to respond quicker than our rational counterpart. He concludes “we do not in the first instance rationalize and verbalize what we smell, but have an immediate reaction to a smell and a tendency to act in accordance with it. In other words…smelling something generally leads to emotionally coloured and sometimes even instinctive actions.”(reproduced by Malnar et al, 2004:132).

Thus traditions set by Plato and expanded by Kant view human rationality as the meaningful way forward, distrusting emotions and aligning particular contempt for smell, reducing it to merely a remnant of our evolutional past, both crude and untrustworthy.

2.7 The invasive qualities of Odour.

A second and more personalised mistrust of odour stems from its manner of perception. Whilst those senses associated with distance; sight and sound; allow us to separate ourselves from our surroundings, odour involves the intimate. It acts without forewarning and invades the body. Taken involuntary into and absorbed by the membranes of the nasal cavity, unlike visual perception that can engender a voyeuristic degree of detachment, we can not close ones nose or block the sensations of a powerful odour until it is too late. It permeates the environment and we are unable to retain our much valued boundaries of personal space, or what Edward T Hall describes in his book, “The Hidden Dimension” as ‘intimate space’. That is, the perceived zone that each person builds for themselves based on their own personal relationship with both their surroundings and other people, in this case, the area restricted solely to those with whom we are intimate (Hall E, 1969). Thus the emotive sense of violation is heightened when, for example, our own airspace is imposed upon by that of another and we are forced to perceive what we may value to be the unpleasant smell of someone else’s perfume, cigarette smoke or body odour. Indeed, it is interesting to note that in “Anatomy of Disgust” by William Miller, the author describes how George Orwell was of the view that the inability to ignore the disgust felt when confronted with the poor body odour of the ‘lower classes’ was the one major obstacle to the success of socialism (Barbara A et al, 2006) .

This notion of ‘invasion’ found form in Western medicine in the concept of ‘miasmas’, or the ability of noxious smelling air to act as a vehicle for disease. During the plague years of the middle-ages, it was commonly held that the breathing in of sweet perfume from honey scented beeswax, dried flowers or herbs would stop the contraction. Bonfires were burnt within infected streets into which scented woods and sulphur would be thrown and scented water would be sprayed around the rooms of those with the disease to stop the pestilence from spreading further. It is interesting to note that Eau De Cologne originated as “plague water” (Barbara A et al, 2006). Whilst it is not suggested that such thinking led as a direct result to the current standing of odours within British Law, planning and architecture, which, as the built expression of the art of society, have all tried to remove us, both perceptually and physically from any possible offensive smells from our day to day experience, it is interesting to note that the first principal act of Parliament aimed at solving the sewage problems of London were in part stimulated by the extent of the fowl stench emanating from the Thames into which the waste of the city flowed and which were making it impossible for Parliament to sit.

2.8 Danger of misleading personal perception

It is perhaps this ability of odours to both invade the body and seemingly have a potentially power effect over our emotions, such as the ability of perfumes to play a powerful component of seduction, that leads to a level of credulity being attached to odours. As Barbara and Perliss suggest in Invisible Architecture, “A Westerner entering a space and smelling lavender will immediately have the feeling that it is an aerated and clean place, even if it is dirty. This exemplifies how the sense of smell can be much more powerful than sight. Here, even if our sense of smell is in conflict with what we see, we instinctively put more credence in what we smell.” (Barbara A et al, 2006: 90). They go on to suggest that this may be why so many expressions and sayings suggesting a level of distrust use olfactory metaphors.

This may suggest why the level of outrage felt at being purposely misled through the use of odour appears far greater than say by visual manipulation. The now clichéd use of the odour of coffee or freshly baked bread in attempting to sell a house appears far more underhand than simply removing furniture to create the appearance of space. This has not stopped the commercial world however from attempting to utilise the ability of odours to trigger emotional responses. Discussing commercial application, Clino Trini Castelli in ‘Invisible Architecture’ talks of the current research being undertaken to try and infuse products, such as cars and electrical goods, with odours specifically with the intention of artificially creating an emotional response within the consumer so as to form a connection with the product (Barbara A et at, 2006). It is interesting to note however that research by R W Moncrieff established that despite the best efforts of those given the task of producing synthetic copies of ‘natural’ smells (in the biological sense), the human nose is still able to distinguish the difference and reject in favour of the authentic (Moncrieff, 1966). This therefore raises questions as to weather the intentional manipulation of odours within the urban framework will only result in suspicion and rejection by those using it?

2.9 Complications and Variations 1 – The External World

Whilst the ability to fix the source of odours in one place can to an extent be achieved, by their very nature, odours are not so easy to control. They exist invisibly within a three dimensional framework and ebb and flow like currents within an ocean, detectable only by the impact and effect they have on third parties like human or animal life, sometimes providing little clue as to their origin. Different odours have the ability to occupy the same space at the same time. Thus we may find ourselves aware of both a constant ambient odour, (which may indeed occupy such a large area that whole neighbourhoods become indelibly associated with the odour) along with the sudden interjection of a strong but quickly passing intermediate odour.

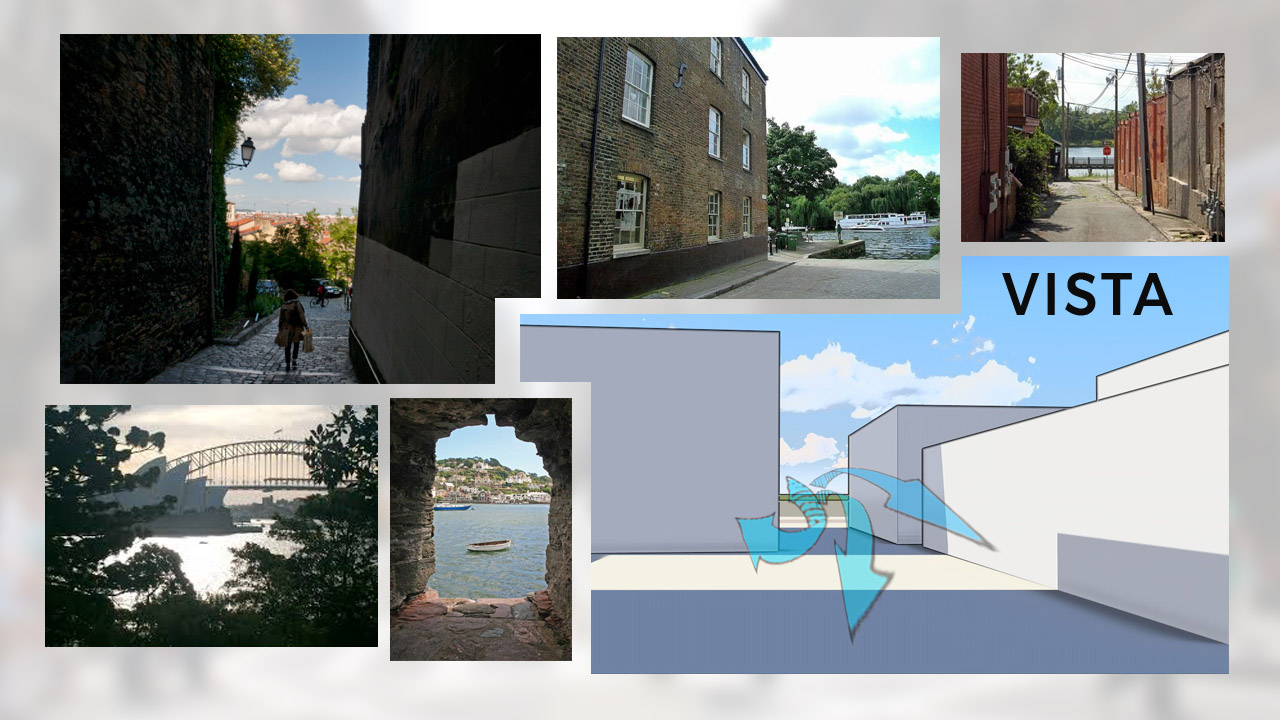

Odours are also at the mercy of numerous, complex and uncontrollable atmospheric variants that influence its movement through space, its strength and duration. Variations in humidity of the air for example can dampen certain odours whilst enlivening others, thus dawn and dusk can be alive with odours which disappear during the remainder of the day, whilst fogs and mists can blanket an entire area with the recognisable, but difficult to describe odour of moist air. The impact of rain and heat can have entirely differently effects within the same piece of townscape, even to individual parts, such as the recognisable odour of wet tarmac after a heavy shower, or the equally recognisable odour of the same tarmac melting under the summer sun, whilst wind and localised air currents can disperse or carry odours far from their original source. Similarly, the physical characteristics of urban form can play a large role, such as its size, shape, orientation or the materials from which it is formed. How does air move through it, does it have the ability to form micro-climates and how is it utilised? Even a strong fragrance can be lost or fragmented in large open spaces, whilst other odours can linger for long period within enclosed and sheltered areas. Thus writing in an article in the late 1980’s, anthropologist Franco La Cecla correctly states that “geography of odours is only possible if we accept that they are fleeting.” (Reproduced by Barbara A et al, 2006: 198).

Another variant factor is the persistence and saturation of the odour source itself. This is often linked to temporal factors. Just as we age, so do odours. The ability of a static source of odour to produce a smell will change and degrade over time as molecules are lost, partially when it comes into contact with the abrasive influence of light, heat and humidity (Barbara A et al, 2006). Urban areas, and in particular major cities, whilst often being perceived as having an individual odour linked to its identity, will also produce a large range of odours that reflect both the countless activities that take place within it, and how these alter through time, be it 24 hour, weekly, monthly or seasonal period. Thus, Porteous correctly states, “any conceptualisation of smellscape must recognize that the perceived smellscape will be non-continuous, fragmentary in space and episodic in time, and limited by the height of our noses from the ground, where smells tend to linger.” (Porteous J, 1990: 25).

2.10 Complications and Variations 2 – The Internal World

In the book “Sensory Design”, Malnar and Vodvarka suggest that ‘place’ as we perceive it, is made up of common elements, but arranged in an individual and interrelated pattern that makes it specific only to itself. In order to gain awareness and comprehend ‘place’, we must not only sense these common elements, but also process and interpret the pattern of these elements in order to spatially construct it within our own perception. They go on to suggest that response to sensory stimulation, or for example one of the common elements within the pattern that happens to be an odour, commonly passes through three stages. The first is what is described as ‘involuntary’ physical response. The second is a response conditioned by our own personal ‘understanding’ or knowledge of the source of the stimulus according to our past experience of it. It is suggested that familiar odours for example are reassuring whilst unfamiliar ones may create a sense of unease or excitement. The last, or ‘mnemonic’ stage is the response to the stimulus if, when identified, it is linked either directly or indirectly with a memory of a particular event or place. It is suggested that this last stage potentially triggers other sensations which, when combined, allows the brain to form a spatio-sensory reconstruction of past experienced places (Malnar J et al, 2004). Examination of research into each of these stages appears to show that each is subject to a large range of possible variances and distortion that suggest both the inherent strength and weakness of odour as a basis on which to build a case for a consistent and useable design tool.

2.11 The ‘Involuntary’ Response

The nose protrudes out into space and its central position, associated chambers, cavities, bones and cartilages, creates a link to all the other facial orifices. The nostrils are set out as a pair in order to aid depth perception, much like the ears and eyes and the many chambers and anti-chambers are lined with hairs and mucus producing membrane designed to acclimatise and clean the incoming air from unwanted particles (Barbara A et al, 2006). Whilst there is still much discussion as to the exact process, it is commonly believed that odours are detected as olfactive molecules hit and attach themselves to ‘docks’ within the membrane, dissolving in the mucus and transferring an electrochemical signal which is detected by sensory detectors. These in turn react to the stimuli and send electrochemical messages along nerve pathways to the olfactory bulb, part of the much older evolutionary lower brain (Sell C, 2007).

Research suggests that the actual differences in odours are produced due to variances in the mixture of olfactory molecules, which differ in shape and form. Certain molecules are more common and attach themselves to the ‘docks’ of the membrane and dissolve before others. Hence, like wine on taste buds, odours can have ‘notes’, waves of subtle nuances, that emerge one after the other as each type of molecule ‘docks’ (reproduced by Barbara A et al, 2006). Another factor is the issue of fatigue. Research conducted by R W Moncrieff suggests that the nose quickly adapts itself to smell, in that the ability of our olfactory apparatus reduces as it becomes saturated by a large influx of any type of olfactive molecules. Thus our ability to perceive a particular odour when in direct contact with it reduces through time (Moncrieff R, 1970). Similarly, perception of odour diminishes and changes as we age. Part of the olfactory system, the Trigeminal nerve, responds to pungent odours (the prickling sensation in the nose). This can become dependent upon response, thus initial aversion to certain odours, such as mustard, horseradish or tobacco; can become pleasurable (Barbara A et al, 2006). Therefore, even at this early stage, perception of odours is not uniform and subject to variances.

2.12 The ‘Understanding’ Response

The second response deals with the change of the incoming information from electrochemical messages into an understandable internal representation of the source of the stimulus. How the brain achieves this is not fully understood. However it has been suggested by Stephen and Rachel Kaplan in “Cognition and Environment” that the principal ability to do so lies within our cognitive capacity to learn and store experiences in the form of internal summaries of patterns and models (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004). Whilst we may utilise the same cognitive processes, the internal summaries formed are subject to each individuals own personal experiences. The olfactory bulb and its pathways are in close proximity and interconnected with those parts of the brain that trigger motivation and emotions, in particular, the limbic system. It is therefore possible that as each summary or pattern is learned, it can be imbued with either negative or positive associations according to the emotional state of the individual at the given time, especially during childhood when most cognition and the building blocks of our perception of the world are being formed (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004). Lorenzo Villoresi, a perfumer working for Santa Maria Novella in Florence has stated “Our tastes are inevitably personal. What we like or dislike depends greatly – beyond the hereditary component that is hard to determine – on our experience with odours in the first years of life. An odour associated with good experiences is “memorized” as being good and likewise for bad odours.” (Barbara A et al, 2006: 194).

That is not to say however that cognitive learning is in itself, completely random, but rather undertaken against a background of cultural emphasis. S and R Kaplan suggest that whilst random positive or negative association may occur, a significant number of smell preferences appear to be learnt, so that associated meanings attached to odours can therefore vary from culture to culture, and that this may well be due to an intrinsic requirement of the cognition process. They suggest that a vital requirement of processing information into representation is to simplify and break it down to an essence. (Malnar J et al, 2004). This is similar to an element of the theory of ‘common elements within interrelated patterns’ advocated by Malnar and Vodvarka, which in turn draws influence from the “law of good continuation” as set out within the visual based Gestalt theory. It is suggested that we have the ability to organise patterns into its clearest and easiest form in order to better understand it. In a sense, similar to the way we focus and clearly interpret only a small fraction of the visual information we receive, allowing images outside of this small area to remain peripheral (Malnar J et al, 2004). E.T. Hall suggests that we do this through a process he describes as “contexting”, and that it is culture which provides us with part of the screening barrier through which the mass of complex information passes. He suggests that in so doing, the individual is protected from an overload of information, allowing meaning and structure to be formed (Malnar J et al, 2004). Our ability to screen in this way exists from birth and is imbedded within our nervous system and sensory organs. Therefore, from an early age we learn from those immediately around us to screen information into what is considered important, and that they in turn form part of a wider collective experience or ‘culture’, which produces and reinforces a continuity of perception and representation (Malnar J et al, 2004).

Culture becomes problematic if attempting to re-enforce meaning due to the possibility that it may not correspond, or worse, fall in direct conflict with the cultural or historic perception of social groups and may lead to alienation and social exclusion. In other words, just whose culture is this? Cultural differences appear to be an extension of basic human behaviour, and that odours were long used as a way of identifying and recognising other members of the same pack or tribe. Who is similar, and therefore to be trusted, and who is not, or what Relph describes as the ‘insider: outsider antinomy’ (reproduced by Porteous, 1990). It is therefore both a system for inclusion and exclusion. Accordingly, what is important therefore is not the odour itself, but rather what its role is within the culture of the person perceiving it. Barbara and Perliss suggest “The smoking room did not arise for reasons of domestic hygiene, but to create a symbolic masculine space laden with all the misogynistic values of Nineteenth-century bourgeois culture.” (Barbara A et al, 2006: 67).

Caution should be stressed however against over emphasising the potential and power of association. In an Odour Preference study conducted by R W Moncrieff in the mid 1960’s, of the 132 odours provided to 12 test subjects, it was also noted that in most instances, people were relatively indifferent to the majority of the odours provided. Only six, including artificial agents that mirrored the smells of bad drains, excrement, bad meat/fish and burnt cooking smells, were universally disliked by all regardless of sex or age and were consistently placed at the bottom of the preference list (Moncrieff R, 1966). Similarly, from personal research, Trygg Engen highlights that few odours, even those generally perceived as unpleasant, will inherently produce a given response, or motivate behaviour. Rather, it is only those odours deemed so obnoxious that will produce violent and ungovernable reactions, perhaps linked back to our basic instinct for survival by avoiding that which may be harmful, causing us to contract our facial muscles, or in extreme instances, requiring us to flee or gag in disgust (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004). Part of the aim of this study will be to test if it is true that we are generally ambivalent to most odours. However, if the vast majority of odours are treated with a degree of indifference, why then should variations in preference of these odours be treated as anything other than a statistical anecdote? Research by C Clifford in the mid 1980’s would appear to indicate that even odour at such a low level of intensity as to not be consciously noted can alter a test subjects spatial judgement and perception of place, so that they maintained of two identical rooms, the one that contained a low level of fragrance was both brighter and cleaner (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004).

Thus with our own personal development of perception, experience and cultural background as a contributing factor, the result is that within each of us exists an idiosyncratic view of the world, that is, as David Abram suggests, “an active and open form, continually improving its relation to things and to the world” (Malnar J et al, 2004: 25).

2.13 The ‘Mnemonic’ Response

The ability of odours to create mnemonic episodes is perhaps its strongest and most interesting attribute, but poses real implications for perception of odours given the implicate highly personalised nature of memories and the often emotional attachment they processes. As Juhani Pallasmaa writes, “A particular smell may make us secretly re-enter a space that has been completely erased from the retinal memory; the nostrils project a forgotten image and we are enticed to enter a vivid daydream.” (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004:135).

Memory in general is a composite of episodic and semantic components, the first relating to the ability to recollect past experienced events, and the second the ability to recognise and link objects or phenomena with its linguistic title. It is suggested in what is known as the Dual Code theory, that when we are able to link both together, such as by both recognising an odour, and being able to name it or its source, it becomes indelible etched into our memory (Reproduced by Barbara A et al, 2006). Studies by Engen and Ross appear to show that whilst initial recognition of odours is often poor, long term recognition of particular odours is far more enduring than those of other senses, such as vision (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004). Research by S. Van Toller and J R King suggests that this may be because of the close proximity of those parts of the brain involved in memory to the olfactory pathways whilst Piet Vroon has suggested that perception of odours has the ability to cause mnemonic impulses at a far greater and deeper level than other senses, to the extent that emotional responses are also triggered (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004). Similarly, research, most recently by Nobel Prize for Medicine winners Richard Axel and Linda Buck suggest that odour is capable of producing such profound reactions in the mood centres of the brain, again due to the close proximity of the limbic system, being the area of the brain that controls emotions and mood states, and the olfactory pathways (Reproduced by Barbara A et al, 2006).

However, as with the previous stages of response, memories naturally are also subject to immeasurable variances of perception. Quite part from the intrinsically personal nature of our own recollections, research also appears to suggest that memories are not static, but are constantly changing and evolving through experience. In the article “Memory and the Making of Places” Frances Downing comments “Memories float, waltz, and flash into our consciousness, welcome or not, infiltrating thought and powering imagination….Rather than a simple repository of experience, memory is dynamic, often seeming to form and reform experience without our conscious permission.” (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004: 21-22). She goes on to say “However powerful a mental image may seem in memory, it does not include all the environmental information contained in any particular place or event experienced. Instead, the mental image presents a version of experience that is most important to the individual or situation at a particular moment in time” (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004: 22). In other words, it can be suggested that the need for reassurance often leads to a warping and shaping of memories in order that we may find a sense of comfort in them. From this, it is therefore easy to understand the concept of nostalgia.

It is interesting to note that it has been suggested that direct experience or memory is not always required for such feelings to occur (Barbra A et al, 2006). Odour would appear to be able to trigger very real emotional responses even when no direct memory exists, such as when they conjure up our own imaginings of a place or time without actual having had direct experience of it, such as the odours of certain exotic foods or perfumes, allowing us to occupy, or at least within our own consciousness, different levels of existence in both time and space (Barbra A et al, 2006). Indeed it is interesting to note that there is a tradition of naming perfumes after the names of romantically linked cities, and so strong is this ability that even the linguistic tag of odours has a degree of power, something that writers and poets have long used to great effect in creating a tangible sense of place or experience through the use of a simple set of well chosen words.

2.14 Resume.

From an examination of the limited available material, it would therefore appear that odour plays a powerful role in our emotional and mnemonic inner lives and as a result, is capable of providing place with a sense of depth and meaning whilst invoking other sensory memories. Further, it can be enormously persuasive and have a large impact upon our behavioural responses. However, it would also appear that these emotional attachments are susceptible to warping and selective re-shaping that call into question any sense of reliability. Its ability to register with our inner most emotional self, has led to its mistrust within Western culture. Coupled with the sheer difficulty of containing or controlling what are after all free spirits, odours, or rather our sense of smell, remain under valued and ignored as a design parameter.

The next chapter therefore sets out the criteria for a number of odour surveys undertaken through a selection of townscapes designed with the intention of exploring at just what level and degree of variety we do perceive odour, and determine if our sense of smell can contain some of the qualities identified with the sense of vision, and thus potentially operate in a similar way as physical characteristics on a behavioural response level, act as a type or motif through emotional response and in doing so contribute to the contextualisation and attachment of meaning to place.

Chapter 3: Enquiry by Survey

3.1 Past Surveys

In order to achieve the stated aims, it was proposed that a number of odour surveys be conducted within a selection of urban forms in order that the extent and responses to odour perception be explored acknowledging the previously outlined variants that exist both within the external world and the internal world of perception. It was noted however that whilst some perception surveys have been undertaken relating to sound, the number of recognised odour surveys is extremely limited and almost without exception deal with the issues of pollution and nuisance, in the main conducted by Government bodies by way of surveying local residents by questionnaire. One such survey was conducted by the City of Toronto in 2004 after complaints about a local treatment plant. Five volunteers from the local community would walk towards the plant from a distance of 2 kilometres in 500 metre increments and measure their own perception as to the intensity of the odour coming from the plant. It is noted however that this provides little guidance as to how a general odour survey should be conducted.

(www.toronto.ca/wes/techservices/involved/wws/htpnic/pdf)

Whilst primitive devises exist that are able to identify and measure the number of odour molecules within laboratory conditions, it is suggested that these in themselves can not replicate the organic olfactory system as they fail to provide the information required, that of the human interpretation of the odours perceived (Malnar J, 2004). It was therefore concluded that for the purpose of the proposed odour surveys, human test subjects would be used. Whilst measurement would be by human interpretation, and therefore subjective, as discussed later in section 3.3, this was not considered inappropriate.

3.2 Survey Requirements

The intention was to undertake two separate sets of survey based on selected townscapes of different chrematistics, one of suburban character, the other a busier city location. By walking through the spaces along a predetermined route, an examination would be made as to the degree, range and intensity of odours within each area, and its impact upon how the areas were perceived, whilst also testing the survey technique itself for possible faults or shortcomings. Given that the intention is to examine if odours can perform both in a similar way as physical characteristics on a behavioural response level, and at a contextualisation level it was considered that the key questions were-

1) Will test subjects perceive the same odour at similar points within the walk?

Despite the physical and temporal variations that can occur, is it possible for an odour to occupy a place to the degree that it is perceived at the same location amongst those taking part in the survey, and thus become a recognised element in the local urban form, even if for a short period?

2) If multiple perceptions occur, is there any correlation between its perception and notable features of the odour or the physical make up of the immediate townscape that may have contributed to this?

If it is found that certain features of townscape or features of odours do create regular patterns of higher levels of perception, especially those with positive associations, should be recorded and noted so that they can be replicated if considered desirable to do so.

3) Can odours be perceived with a degree of clarity?

Despite variations, the movement of air and the movement of the test subjects through the space, can ‘notes’ within odours be detected, in a similar way to the finer architectural details of a building?

4) How strongly do building and facing materials contribute to the number and range of perceived odours?

The ability of certain planting to produce odours at a high level through soft landscaping is well established. However, the ability of building and facing materials to produce and contribute to the range of townscape odours is less well known.

5) Will any of the Odours produce an emotional or mnemonic response?

Given that research appears to suggest that an emotional response is likely to effect your perception of a place and aid mental mapping, what proportion of sensory responses will occur at the ‘involuntary’ level and what at the deeper ‘Mnemonic’ level.

6) Do odours and their level of complexity contribute to the integral character and identity of place and if so does this add a new level of meaning and understanding of the space?

This is intended to question whether odours do indeed place a significant role in adding to the contextual character of place and aid in the mental mapping process, and whether the degree and complexity of stimulation plays any part in how comfortable people feel within it.

3.3 The suitability of Phenomenology

The use of human test subjects produces a number of significant problems in the validity of odour surveys, principally relating to issue of subjectivity. However, the use of Phenomenology is now well established within the sphere of humanist studies. Formulated by Edmund Husserl in the early 20th Century, phenomenal reality removes the distinction between “subjective” and “objective” realities, and that what remains is a consensus formed from a matrix of sensations and perceptions (Malnar J et al, 2004). Whilst Malnar and Vodvarka point out, “It has been argued that the aesthetic response is primarily a function of cognition, that art and architecture are best “understood” intellectually” (Malnar J et al, 2004: 26). However, humanists such as David Seamon reject this as elitist and take the view that when appreciating or finding meaning within a space, we do so through many different aspects of sensory perception, how it appears, smells or makes us feel. It is sensory experience that allows us to understand our surroundings, and as such, a phenomenological approach, which exams and describes direct, conscious and sensorial experience, rather than objectified quantification, that should be used when attempting to quantify the form of the world through perception.

This approach however creates problems. Unlike the quantifiable sciences and traditional western philosophy, by accepting subjectivity, it also removes the fixed definable “datum” that stands outside of personal perception. There is no definable bench mark against which things can be measured. It thus strays from the controlled parameters of scientific rigour and as Engen argues, is in danger of being dismissed as being merely ‘descriptive’ and ‘anecdotal’ (Reproduced by Porteous J, 1990). However, within the spheres of behaviour research and design, the use of phenomenology is accepted on the basis that the aim is most often related to the search for meaning rather than causes (Malnar J et al, 2004). Individual perception, sensory responses and ones own experiences are not bound by predefinitions of reality and as such, if an odour is perceived, then it is real to the one perceiving it. Phenomenology allows for a more open ended and holistic view of the world to be developed by accepting the sensory experience as being as real as other supposed certainties, and thus allowing for its random and unreliable aspect, as opposed to the ridged boundaries of functionalism. Indeed, Seamon goes on to suggest that “Architects and other designers have become interested in phenomenology largely because of a practical crisis; the frequent failure of both architecture formalism and functionalism to create vital, humane environments” (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004: 230). It is therefore considered that the use of a phenomenology approach, within otherwise controlled boundaries, is an acceptable approach to take in this instance.

3.4 Producing Classification

One of the identified problems of attempting to examine and describe sensory and conscious experience through survey is the lack of a recognised system of denomination, grading and classification (Malnar J et al, 2004). This in part is due to the difficulty often experienced in verbally expressing the olfactory sensation. We often struggle to find the right words to describe an odour, what Lawless and Engen term as the “tip-of-the-nose” problem (Reproduced by Porteous J, 1990: 26). It has been suggested that this may be due to the olfactory bulb being located some distance from, and having few direct links with the left neocortex of the brain which deals with language (Barbara A et al, 2006). Indeed it is noted that when attempting to describe an odour, there is often reliance upon adjectives used to describe other senses experiences, so that odours can be sweet, rancid, strong, heavy, hot, melodious and dark for example.

A more problematic issue is that to date there still also remains no accepted or uniformly utilised basic system of classification. There are approximately some 400,000 existing odours compounds, the vast majority of these the result of synthetic production (Porteous J, 1990). In order to provide some degree of workable order of odours, there have been numerous attempts to categorise them into common groups, especially those occurring within the daily experience, from as far back as 400 BC and Aristotle. These have ranged from a minimum of four categories up to forty four, with each often being conceived from an earlier classification but one which was perceived not to be quite correct. The first task therefore was to examine those most commonly used attempts at previous categorisation and to either utilise an existing one, or draw up a new one based on a range of both natural and synthetic odours that was felt were likely to be present within the built environment. Previous categorises identified by Barbara, Moncreiff, Perliss and Porteous included;

Sweet, Acid, Austere, Greasy, Acerbic, Fetid – (Aristotle 400 BC) (Barbara A et al, 2006);

Aromatic, Fragrant, Ambrosia (musky), Alliaceous (garlicky), Hircine (goat), Foul, Nauseous – (Linnaeus 1756) (Porteous J, 1990);

18 categories primarily intended for perfume production including Rose, Balsam, Vanilla, Camphor, Citrus, Eugenol (clove), Mint – (Rimmel 1800’s) (Barbara A et al, 2006);

Fresh, Close (or suffocating), Nauseous, Sweet, Stink, Pungent, Ethereal and Appetising – (Bain 1855) (Moncrieff R, 1966);

Ethereal, Aromatic, Fragrant, Ambrosial, Alliaceous, Empyreumatic ((burnt vegetables and meat), Hircine, Repulsive and Nauseating – (Zwaardemaker 1895) (Moncrieff R, 1966);

Fragrant, Putrid, Ethereal, Burnt, Spiced, Resinous – (Hennig 1916) (Barbara A et al, 2006);

Acrid, Rotten, Foetid, Burning, Spicy, Ethereal, Garlicky – (Heyninx 1919) (Porteous J, 1990);

Fragrant, Acid, Burnt, Goaty – (Crocker-Henderson 1927) (Porteous J, 1990);

Floral, Balsamic, Fruity, Empyreumatic, Comestible, Woody, Rustic, Repellent – (Billot 1962) (Barbara A et al, 2006);

Ethereal, Floral, Musky, Pepperminty, Camphoraceous (fruity), Pungent, Putrid – (Amoore 1970) (Porteous J, 1990);

Ethereal, Garlicky, Acerbic, Rancid, Burnt, Aromatic, Floral, Woody, Musky, Nauseating – (Boelens 1974) (Barbara A et al, 2006).

It appears that these various and often contradicting attempts to classify or rank odours is a result of the subtleties of odour. Everyday experience would suggest that certain odours do not fall comfortably into a particular class, but rather act as a bridge, so that a gradual merging of one class into another occurs. Certainly most classes do not sit separate from others. However, it was considered that for practical reasons, a degree of simplification would have to be employed in order to produce a workable system. Whilst this might lead to some confusion or disagreement by those undertaking odour surveys as to what classification a particular smell should be labelled under, it was considered likely that this would only occur infrequently and that odour classifications could be altered if clearly at odds with general consensus. A more identifiable problem however related to the use of titles of classification that were either considered archaic or which would not be clearly understood or associated with groups of odours by those conducting the survey. This would include previous classifications such as Ambrosia and Austere for example. Other classifications included categories that were either intended to be used only in the production of perfumes or others, such as Hircine or Eugenol, that were not considered likely to appear regularly within the modern western urban environment.

Therefore, it was decided to create a new set of odour classifications, based heavily on those groups of previous systems and incorporating the concept of including groups for both pleasant and unpleasant odours, but one which attempted to focus classification into groups of odours likely to occur within the urban environment, and which were as user friendly as possible so that group titles could be easily recognised and understood by those conducting the survey. It was noted that previous classifications tended to group around the use of 7 to 8 categories. Whilst it was considered important to limit the number of categories to a manageable level, it was felt that restricting the number of groups to four or five would render it a needlessly blunt tool with little scope for nuance. A list of 11 categories was produced, based on natural elements (wood, earth, water, flora), altered, processed or distilled elements (resins, conflates, agro-products), human activity (comestibles, some decomposition) and involuntary reactive odours (nauseating).

The categories were thus;

Woody– Trees, leaves, bark, untreated wood.

Floral– Flowers, Pollens, Sweet fragrances.

Earthy– Damp Soil, Leaf litter, Mud, Stale Water, Grass, Stone, Brick.

Fruity– Fruit, Sun creams, Hair Products.

Resinous– Plastics, Preservatives, Creosote, Rubber, Paint, Paraffin, Petrol, Tar, Oil.

Nauseating– Sewers, Excreta, Ammonia, Vomit.

Ethereal– Fresh Water, Mist, Fog, Airy, Lightness.

Aromatic– Spicy, Pungent, Herbs, Incense, Certain Woods such as Sandalwood.

Comestibles – Food, cooking smells.

Burnt– Smoke, Charcoal, Coal.

Rancid – Decomposing Fats and Oils, Rubbish.

From this list, it was hoped that results would be registered across many of the categories, in particular those dealing with the physical constructs of the urban form, such as Resinous, Earthy and Ethereal, and those dealing with activities, such as Comestibles. It was acknowledged however that odours conceivably falling within the categories of Nauseating, Burnt and Rancid were less likely to appear due to the perceived general unpleasant connotations associated with odours, and thus the likely management of their sources through methods of control.

3.5 Recording and Schematics

As has previously been stated, one of the intended aims was to discover if odours can act in a similar way to physical forms and weather our sense of smell can in anyway act like our sense of vision. As such, when attempting to create a notation system for expressing the olfactory sensation, it was considered that existing understanding relating to the process of visual perception may be of assistance. It was considered that whilst visual sense differs from the olfactory in many ways, not least that the eye enquiries by seeking out information, whilst the nose is merely presented with odours, both appear to enquire and grade the information it receives.

Humans rely on shapes and colour for distinguishing objects and as such, the eye is constantly scanning its surroundings, focusing on some points and seeking out detail of interest when stimulated, whilst allowing other points to remain peripheral, their perception noted and understood merely through cognition (Porteous J, 1990). Jean Piaget suggests that in visual perception, “space, as constituted by a collection of objects, is not homogeneous; even in the case of objects of equal size…some are over– and others under-estimated as a function of the five following factors; the area of the retina which they stimulate (central or peripheral); the duration of their centration; the temporal order of their centration; the intensity of their centration (attention); and their visual clarity; as a function of illumination, distance from the observer, etc” (Reproduced by Malnar J et al, 2004: 244). He goes on to suggest that these structures of perception may be equally transferable to other senses.

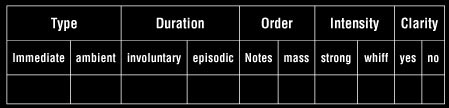

Taking Piaget’s terminology, Malnar and Vodvarka produced a vocabulary schematic to form a matrix of common aspects of sensory response as it relates to space and it is from this that guidance was sought. Using their interpretation of Piaget’s distinctions, it was possible to suggest a realignment of the structures of perception to apply to the olfactory sense. This is best explained by first setting out the suggested common aspects of visual response to an object thus –

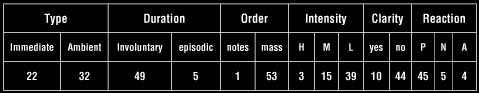

TYPE – The area of the retina which is stimulated (central or the peripheral?)

DURATION – How long are you stimulated by it (remain focused or subliminal)?

ORDER – Sequence of information (do you take in its detail or its mass?)

INTENSITY – How bright is it?

CLARITY – Its contrast.

Secondly, to take the same set of common aspects, but applied instead to sensory responses within the olfactory system thus –

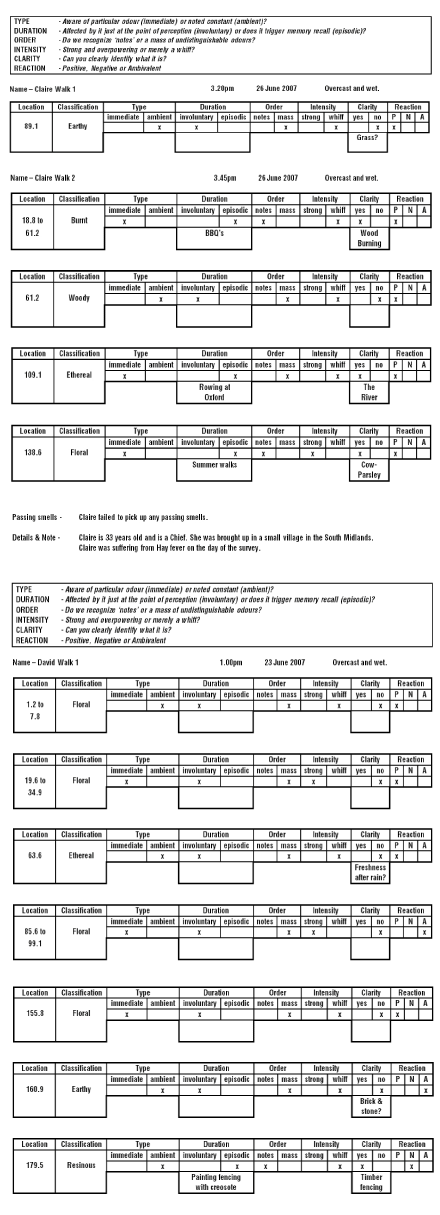

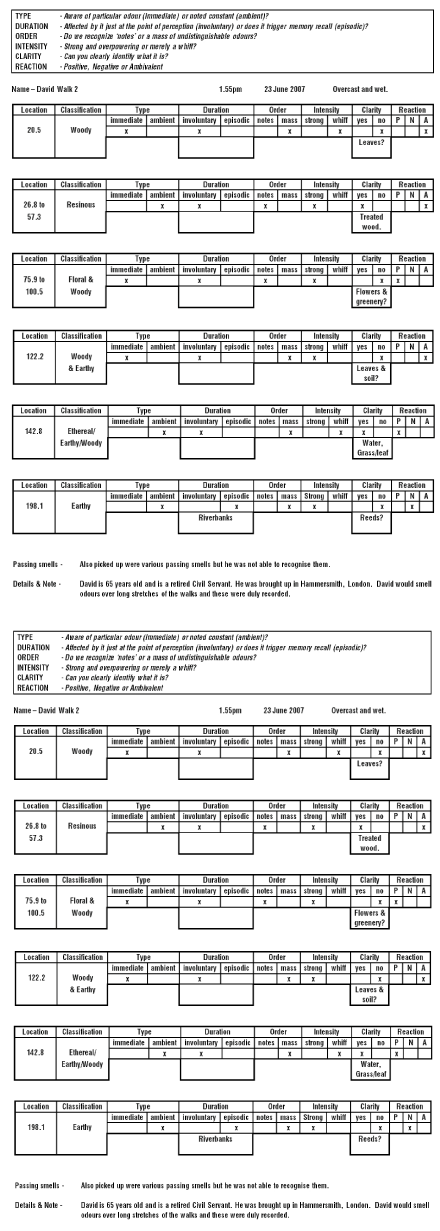

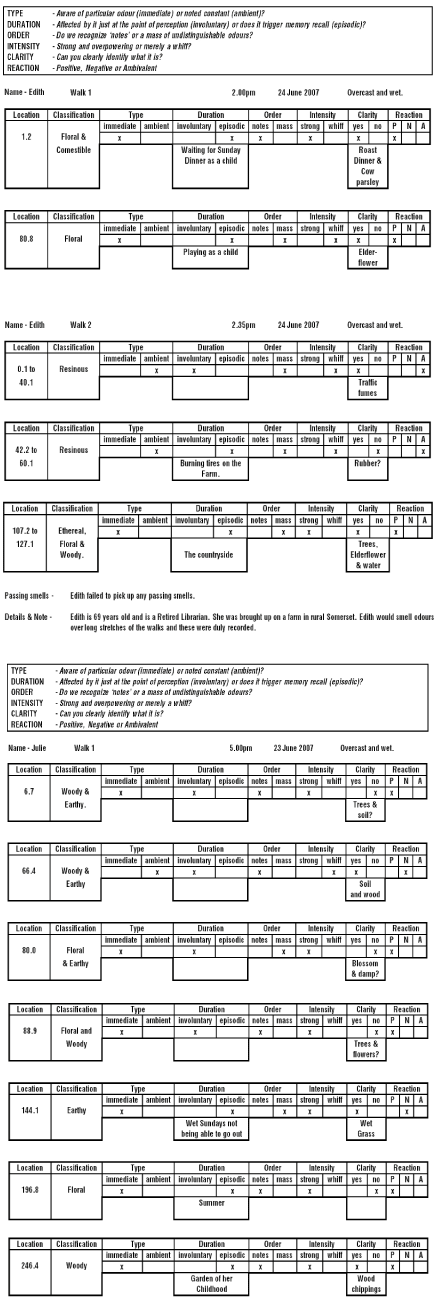

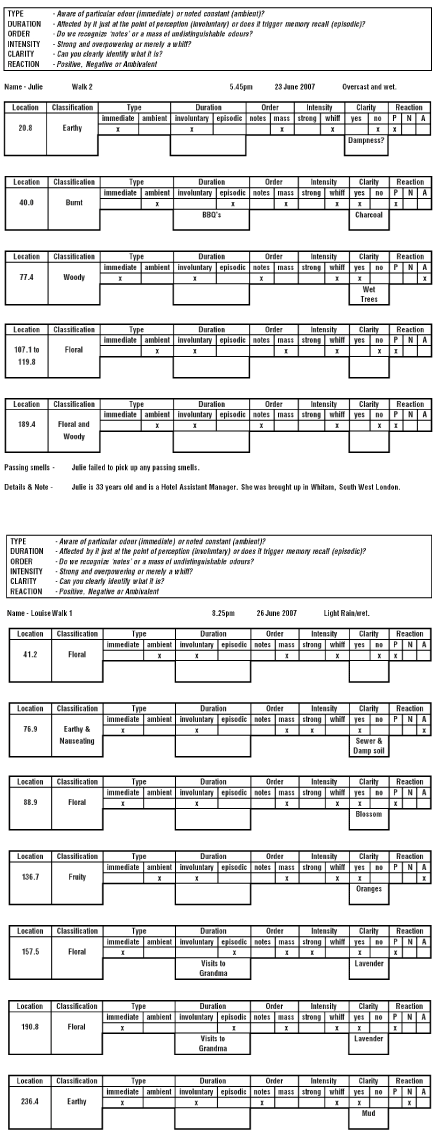

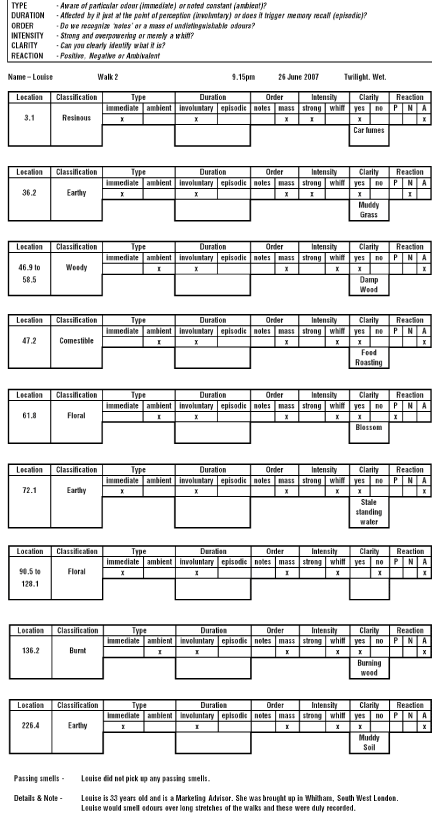

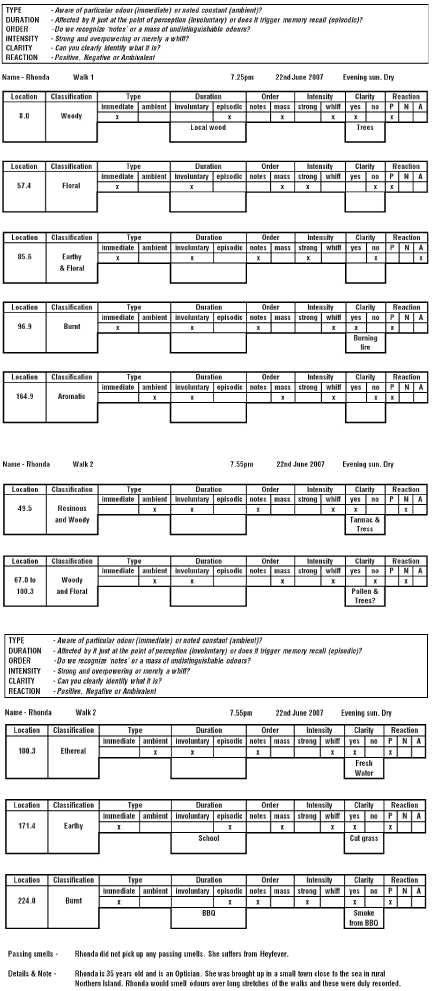

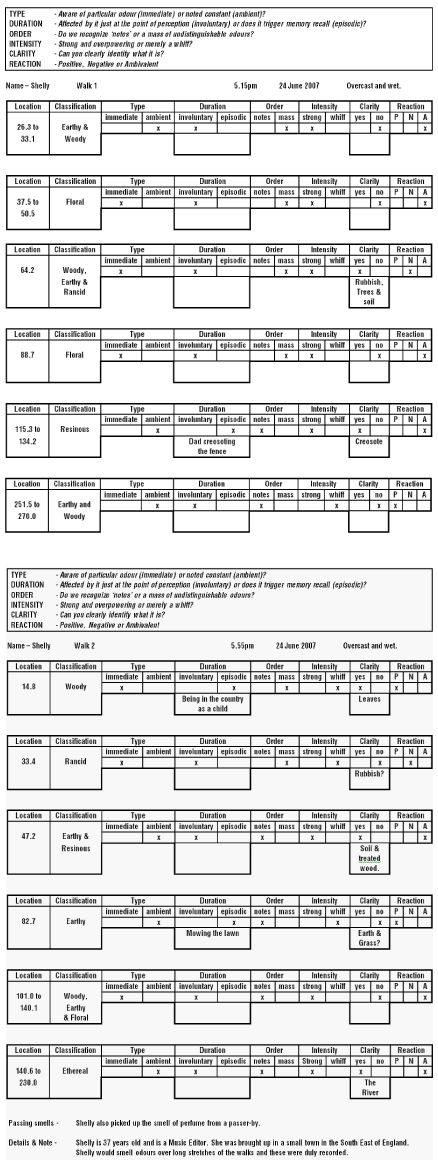

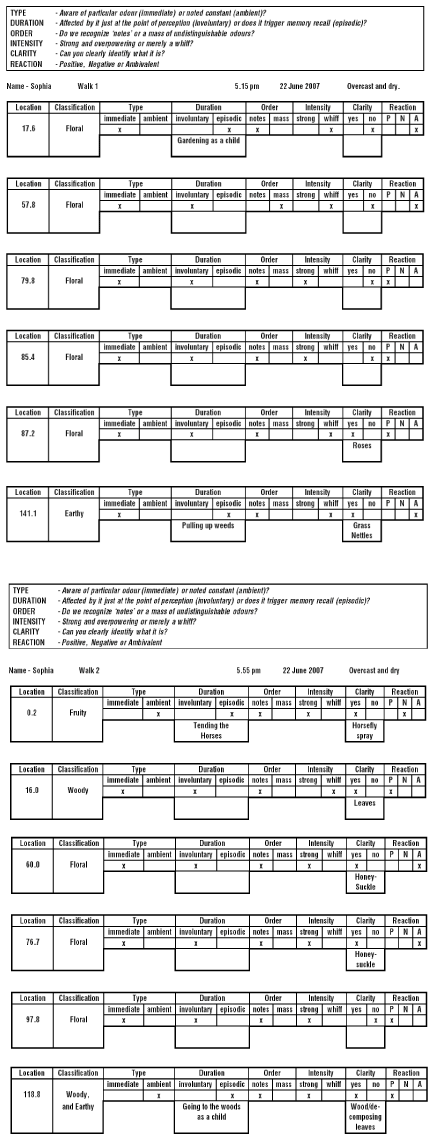

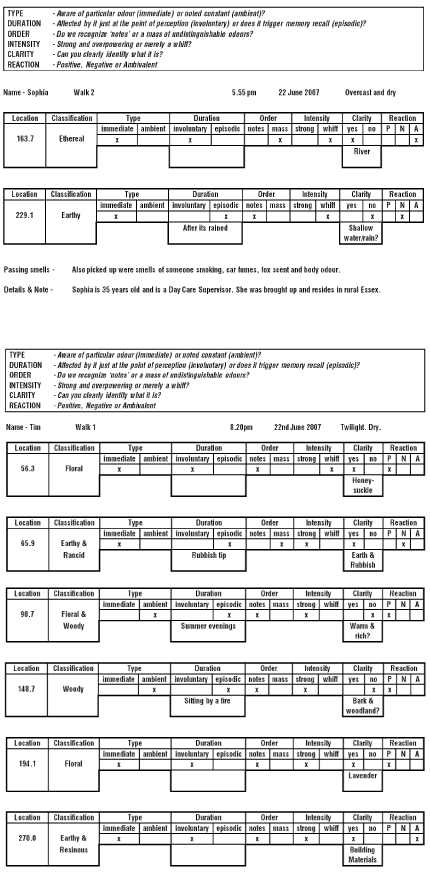

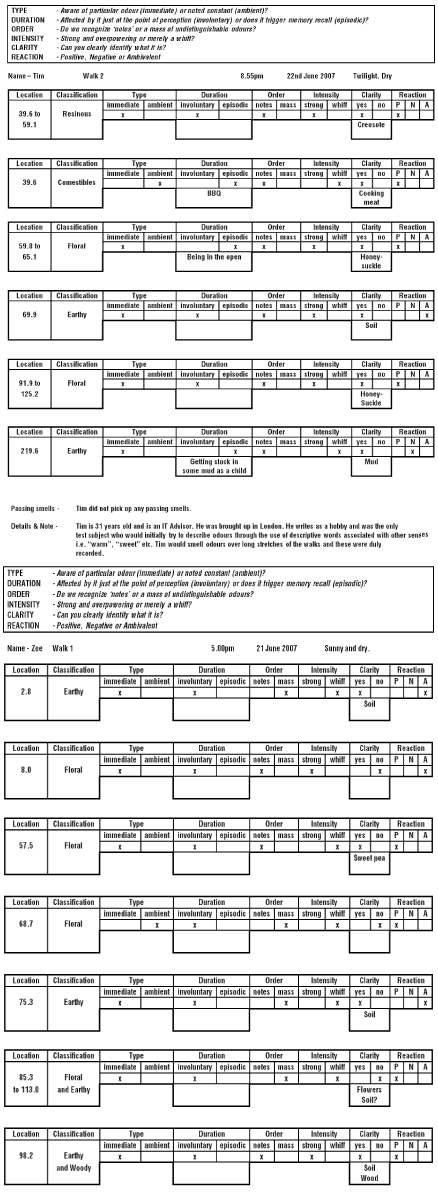

TYPE – Is the odour suddenly there and central within your level of perception (immediate) or a noted constant (ambient)?

DURATION – Length of affect? Just at the point of perception (involuntary) or does it trigger memory recall (episodic)?

ORDER – Do you recognize ‘notes’ or a mass of not easily distinguishable odours?

INTENSITY – Is it strong and overpowering or merely a whiff?

CLARITY – Can you clearly identify what the source of the odour is?

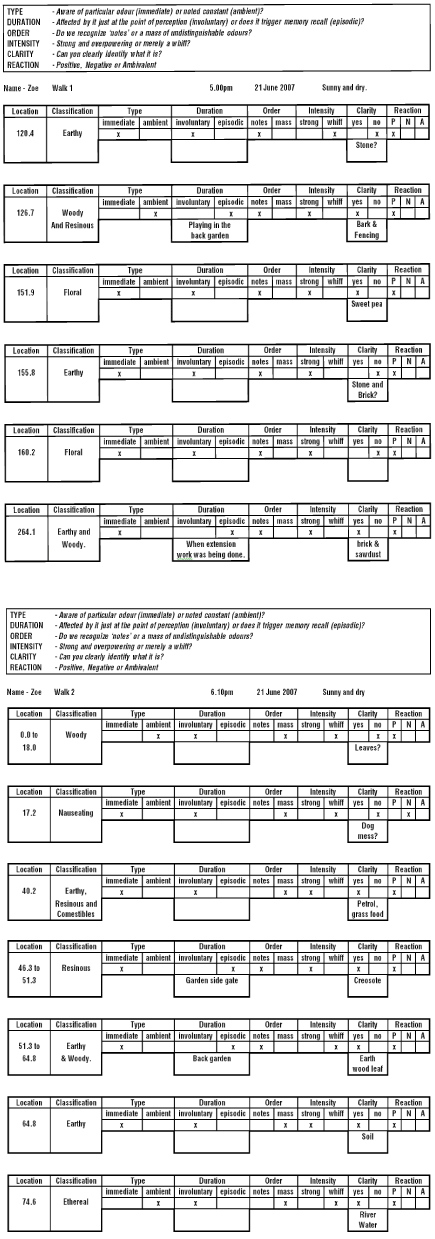

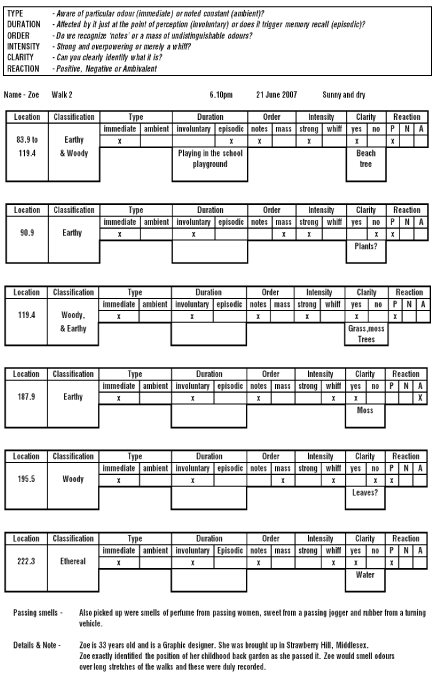

In order that these common aspects be applied in such a way so as to meet the stated aims of the survey, whilst also keeping it as simplistic as possible, it was therefore proposed that perception of an odour event be interrogated through the use of the above series of questions and notated with a simple ‘tick’ process thus;

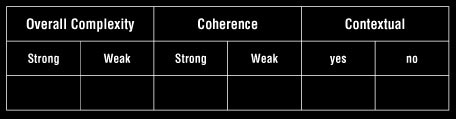

Figure 1. Q & A at point of perception.

In addition, it was proposed to notate the precise location at which individual odours were perceived in order to answer question 1, that is, would the test subjects smell the same odour at the same locations; ask the test subject to place the odour within one of the categories as set out above so as to test the classification system; and lastly to ask if the test subject experienced either a positive, negative or ambivalent reaction through the perception of the odour, in order to ascertain whether certain odours were able to produce an emotional response and if any particular odours produced similar response across the group.

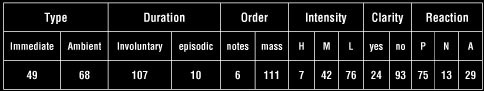

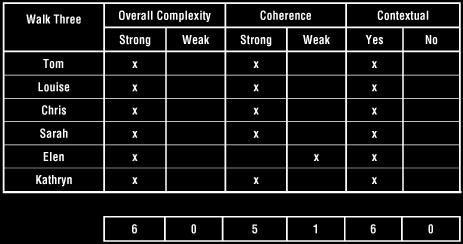

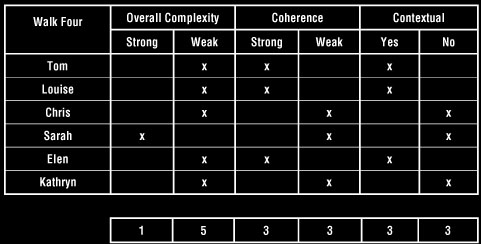

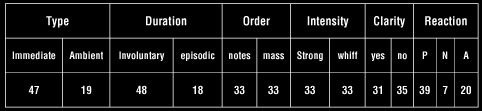

The above were therefore intended to provide a reasonably detailed and notated examination of individual odours. However, it was also considered necessary to determine if the presence of odours had in any way influenced the test subject’s perception of the space as a whole, and that if this was influenced by the range and relative complexity of the odours sensed. Again, this is best explained by first using parallel questions in terms of the visual understanding of a townscape. Therefore, to what extent do individual buildings forming the townscape vary in size, form and style? Given this level of variation, to what extent is there a sense of coherence within the built form, even if consisting of different individual elements? Lastly, do the buildings, both individually and when viewed as a mass contribute to the integral character and identity of the urban environment? In other words, do the buildings influence the perceived legibility of the area? Again, a schematic produced by Malner and Vodvarka, this time relating to legibility, was used for guidance based on levels of complexity, coherence and contextualisation (Malnar J et al, 2004). Substituting buildings for odour, the following is produced:

OVERALL COMPLEXITY – did the walk consist of many intricate odours?

COHERENCE – were odours coherent with each other?

CONTEXTUAL – did odours contribute to the integral character and identity of the place?

Therefore, after each test subject had completed a walk, it was proposed to ask the above questions and to again to notated it with a simple ‘tick’ process thus –

Figure 2: Q & A upon completion of Odour survey.

Chapter 4: The Odour Surveys

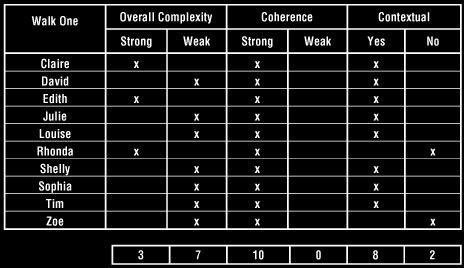

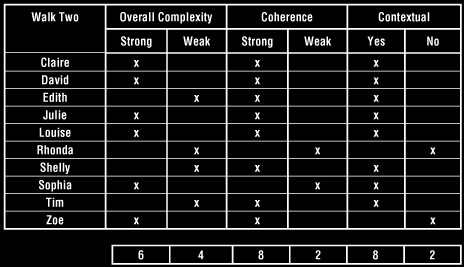

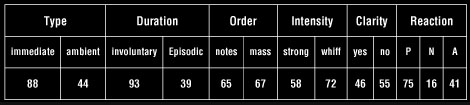

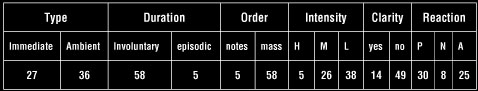

4.1 Suburban Townscape – The Survey Conditions

The first set of odour surveys were undertaken by 10 test subjects, consisting of friends and acquaintances, each taking the survey individually. The surveys consisted of two walks located some 200 metres from each other. Both were located in East Twickenham, Richmond close to the River Thames at Richmond Bridge. The first walk measured 270 metres; the second 240 metres from set ‘start’ and ‘stop’ points, and the surveys were undertaken over a period of 7 days in mid-June. Whilst it was hoped that surveys would be undertaken at similar times of the day it soon became apparent that arranging for a large number of people to be at a set place at a set time would not be possible. Therefore whilst most surveys were conducted during the hours of late afternoon to early evening, a small number took place during the early afternoon. Similarly, whilst weather conditions were in the main similar, that is largely warm but overcast, some minor variations did occur such as light rain during one survey walk. In order to retain some degree of continuity, one survey was also abandoned due to heavy rainfall, carried out instead on the following day.

Each test subject was guided along a central route through the set walks, with progress, questioning and recording undertaken using a calibrated Trumetre and the pre-produced survey sheets. The subjects were blindfolded, in order to exclude visual stimuli or clues to possible odour sources. Whilst accepting that other stimuli such as noise, heat, air movement and gradients can effect ones perception, it was considered that visual stimuli represented the most immediate and practicable sense to exclude. The routes of the walks were not disclosed.

Subjects were briefed that it was not a test of their olfactory capability, and were requested to walk at a reasonable pace comfortable to them, given that whilst blindfolded, they were being guided by the arm. It was thus intended that subjects should not be attempting to studiously pick up every single odour and provide a ‘high score’ in order to please the co-ordinator. When subjects indicated that they had perceived an odour or that an ambient odour had suddenly grown in intensity, the walk would pause, the exact location was noted and the first set of questions relating to individual odours were asked. At the completion of each walk, the blindfold would be removed and the second sets of questions relating to legibility were asked.

4.2 Walk One – Description

Walk One consisted of a 270 metre route through a continuous, predominantly pedestrian only pathway that runs behind residential and houseboat development on the west bank of the Thames at Richmond. Commonly known as Ducks Walk, the pathway followed is for the most part between 3 to 5 metres in width and enclosed by a variety of fences, brick walls and semi-mature planting. Along one stretch (at points 137 to 224 metres) it forms part of a wider vehicular access to riverside residential developments while at another (points 80 to 92 metres) it runs adjacent to the end point of a residential road. Popular with local residents and bike riders, it is characterised by its suburban calm and relative sense of quiet in comparison to the busy Richmond riverside on the opposite bank due to the lack of traffic and the high level of semi and mature planting including a significant number of trees which overhang the pathway.

It was identified as a suitable place for survey due to a number of facets. First, it should be noted that it was not the intention to rely solely on areas of townscape that had clear associations with high or complex levels of odours, but rather to study a range including those that might be considered relatively neutral in terms of odour association, such as a typical suburban environment. Thus it was intended to examine if these areas were indeed neutral or largely free from odours or whether even these areas contained some degree of odour character. It was also both easily accessible so that surveys could be undertaken over a number of days and relatively quiet, allowing test subjects to feel at ease in the otherwise uncomfortable position of being blindfolded.

It was envisaged that the potential for odour production was likely to occur predominantly by materials rather than uses. Ducks Walk contains both fenced pedestrian walkways as well as open areas of active frontage to residential properties. A variety of building and facing materials have been utilised to the enclosure of the pathway, such as timber fencing and brick walls, as well as areas of planting. Similarly, the footpath varied from tarmac to paving stone as well as containing small areas of both managed and natural planting such as grass and hedging. In addition a number of residential properties have utilised different forms of parking surfaces to front areas, such as gravel and concrete tiles, and one property at the time of the survey was in the process of substantial alterations and extension, resulting in storage of building materials within the front and rear gardens.

It was considered therefore that the proposed route passed through a typical, if reasonably varied suburban area which whilst not containing an extensive or unusual range of building or landscaping materials, did appear to provide potential for some variety of odours. Similarly, the route included ‘pinch-points’ within the townscape which produced areas of relative enclosure, as well as areas of relative openness. It was therefore considered that these variances in townscape may also provide potential for differences in odour strengths if it was indeed the case that areas of enclosure were able to retain odours due to their potential to produce micro pockets of stillness within wider air currents.

4.3 Initial Results