Drivers of Urban Dynamism

Nick Booth

“Urban Dynamics” as described by Aldo Rossi is not a modern feature. The urban skeleton has and will continue to be the subject of renewal and change as patterns of development are shaped by the shifting currents and emerging influences within political, social, technological, aesthetics and economic spectrums. The “Informational” or “Post Industrial” city is the latest and perhaps the most radical force for transformation to occur on the urban form since the Industrial Revolution. This has recently been joined by an increasing drive for an “intensification” of the urban form. From first examination, it would appear that one derives strength from its non-reliance upon the urban form, while the other seeks its renaissance so that it may re-establish its importance. Is one therefore a reaction against the other, or is the emerging intensification of the urban form the first real expression of the information city? To answer this, I intend to examine the drivers and features of the current trend towards intensification that directly relate and interact with the features of the “information city” albeit from the perspective of the developed economies of Western Europe, the United Kingdom in particular.

It should be briefly recognised that there are interconnected driving forces for ‘intensification’ that whilst forming part of the emerging ‘intensification’ movement, do not directly relate to or are a direct response to the growth of the ‘information city’. These include sustainability, the housing backlog, changing demographics, spiralling land values, fashion and culture. ‘Sustainable Communities’ (2003), the ‘Urban Task Force’ (1999) and ‘The Compact City’ Movement (Jenks 1996) for example have produced a raft of guidance aimed at producing an intensive and sustainable urban form, without necessarily providing guidance on the built form that achieves it. Their contribution cannot be over emphasised, but for the sake of brevity, they will stay in the background in this instance.

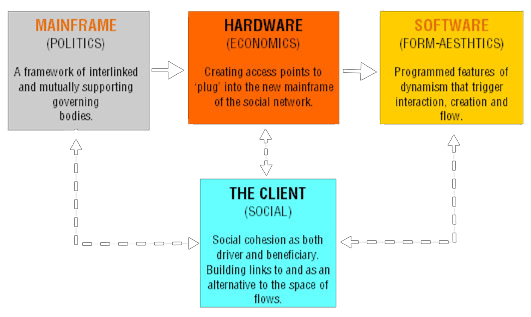

A thorough analysis of the tangible effects and attributes of the information age was conducted by Manuel Castells in order to better understand the meaning of the new paradigm of a “space of flows, superseding the meaning of the space of places” (Castells, 1989: 348). Castells’ research leads him to conclude that there is a “destructive dynamic” arising from this, which needs to be deliberately countered by “the reconstruction of place-based social meaning” (Castells, 1989: 350). He suggests that this imperative be articulated at three levels: political, economic and social, from which issues relating to form and aesthetics also spring. For the purpose of this essay I shall therefore examine each of these in order of perceived importance, lastly expanding upon the social features of ‘intensification’, showing how features are interlinked and dependent upon each other.

Political

One of the principal features of the ‘post industrial’ or ‘informational city’ is that power holding has shifted to organisations not bound by locale and who are interconnected with similar organisations through an infrastructure not readily available or identifiable to those not within the same flow of information. This has led to the possible dislocation of place-based societies and their elected representatives from the organisations of power and production. Increasingly, information becomes a mode of development, and economic restructuring is removed from the hands of National Governments. In response, it can be suggested that Governments identify ‘intensification’ as a dynamic tool for developing a central role in restoring the meaning and social control of places. Restoring control of the development process so that an alternative “space of flows” is derived from the physical rather than the virtual. This has been supported by central bodies such as the European Union seeking to expand internet links within a social perspective with its eEurope Initiative in 2005. This took the view that internet access was a fundamental right for all European citizens and sought to put “the European Stamp on the Internet” (2005). When local governing bodies seek to utilise the free flow of information and form connections with similar governing bodies, such as Birmingham City Council chose to do in the 1990’s by forming multiple links with new partners through the European Union, the intensive urban form could provide part of a new social-spatial structure, or mainframe, able to produce, control and shape flows of production and thus economic development.

Economic

Notwithstanding some of the economic benefits associated with an intense urban framework (efficiencies of infrastructure, reduced resource consumption, transport, opportunities for planning gain etc), ‘Intensification’ as renaissance of the city can also be seen as a politicised attempt to market the city as an economic factor. Despite the freedom from place associated with the ‘unbounded’ information age, it still largely operates within the existing urban form, relying on pre-existing centres of communication and population. ‘Knowledge’ and ‘Intelligence” are key commodities, with productivity linked to the capacity for the creation and processing of information. In such an economy, the primary resource and potential for future growth is very much linked to the talents of a happy and stimulated workforce (Castells 1989). In contrast to a segregated and inert society, ‘intensification’ has been linked to interaction and diversity, a place of cultural mixture and depth of meaning. It represents both an attractive place to be as well as a place where a free exchange of ideas and information can occur in the physical as well as the virtual world. The Urban structure therefore becomes a ‘transfer network’ and the user a receptor, in many ways resembling the Coffee Houses of 17th Century London, where the streets and informal meeting places became the trading floor of the new mercantile capitalism. It has the critical mass to support a social milieu that constantly stimulates intellectual development, and which allows for the interweaving or collision of the various strands that make up what Graham Shane describes as ‘the net city’ (Shane 2005). As such, localities such as the intensive built form becomes an indispensable element, both a selling point by which local economies can attract and retain information based markets and a system through which the new links can be ‘plugged’ into. It therefore acts perhaps as the operational hardware within the new social-spatial mainframe.

Form and Aesthetics

A high-density cityscape in itself is not sufficient for the successful economic marketing of the new spatial-social network. The danger of town cramming apart, and the need to provide a comfortable and safe environment in which to live, intensive new places must also have a unique selling point. Much debate has occurred as to what the vibrant ‘intensive city’ would appear like. Dutch urbanist, Rem Koolhaus, for example suggests that it best be described as ‘intensivity’, created through a chaotic collage of urban experiences. Certainly however, it is considered that there are several key requirements. A mixture and fine grain of land uses removes the traditional urban segregation. Juxtaposition and contiguous mixed-use development forms part of the excitement and increases the occurrence and potential for exchange. The place of work, residence and entertainment therefore may all exist within the same neighbourhood, street or perhaps building, especially if all have access to the virtual networks, allowing anyone to ‘plug in’, hot-desk or work from home, blurring both the physical and conscious boundaries between ‘home’ and ‘work’. Buildings themselves are no longer stand-alone structures, rather a flexible and multi-tasking space within a wider supporting framework (Habraken 1972). Design of dynamics allows for the physical form to be produced, reduced or enlarged by the activity within. At street level, flexibility is paramount, creating a vibrant changing pattern of organised informality serving many actors, whilst intensity is increased by punctuation of the surface area and high levels of connectivity and accessibility, perhaps through both vertical and parallel movement systems. Design, architecture and physical form similarly is open to re-interpretations, perhaps limited only to coding set within a robust development framework. It may follow that all features are flexible enough to allow for constant refinement and adaptability according to ‘feedback’ within a partly self-organising ‘rhizomic assemblage’ (Bertalanffy 1976), that is, where no one voice dominates, albeit, according to how much freedom the principal ‘city actor’ at that given time allows. Aesthetics and design therefore may play the role of defining the selling point of each neighbourhood depending upon the desires of its local governing bodies, taking an intrinsic role in the successful operation of the intense urban form, acting indeed as the software within the wider political and economic mainframe and hardware.

Fig 1. The social-economic based resistance against the ‘space of flows’ through the creation of an alternative interlinked framework with ‘intensification’ as trigger of re-establishment of the ‘space of place’.

Social

Lastly, what of the social aspect of ‘intensification’? It could be argued that all of the above is achievable and can only be considered a success if it re-enforces social and cultural cohesion. Indeed, as shown on Fig 1, the client of the process can be viewed as the urban communities that may directly suffer through economic isolation and the disintegration of the social fabric. Despite technological advances, access to the advantages of the new ‘time-space compression’ is not universal, restricted by unequal distribution of economic resources, and what O’Byrne (1997) describes as the lack of cultural capital within working class communities. There is clearly the hope that a more intense urban framework will not only re-establish the importance of place, but also allow new opportunities to be presented to the currently disenfranchised, in particular those associated with the new informational industries. However, as the first wave of ‘intensification’ is likely to occur within areas considered suitable also for regeneration, the danger is that despite the above, little credence will be paid to existing communities that are perceived as failing to justify their existence as part of the new ‘space of flows’. Issues of displacement and the appropriation of identity through re-branding have already occurred in the Dockland development of east London.

“Place” is particularly important when discussing the concept of “the working class” (although it should be remembered that the definition is a political construct). Research by Hoggart as far back as 1957 described working class culture and identity as being far more rooted in ‘the local’; existing spaces and the meanings attached to them (reproduced O’Bryan 1997). Bourke suggests that such communities utilise a self-imposed segregation in which the sharing of experiences is an act of solidarity or commonality. Cultural identity and cohesion is heavily associated with the certainty of place, and communal spaces, in particular those that mark boundaries are given particular meaning, often associated with defence against other classes or ‘outside’ authority (reproduced O’Bryan 1997). Therefore, as the perceptions of spatial barriers are eroded, those within communities reliant upon spatial security as part of their defence against the outside world become ever more threatened by the fear of displacement. As O’Bryan (1997) suggests however, even within the most isolated communities, the construction of ‘locality’ can be a fluent social process. ‘Intensification’ should therefore be viewed as an opportunity to re-link such communities regardless of their perceived role within the information age, but only when governing bodies act as true agents of social development, through the clear understanding, support and participation of the local community. ‘Intensification’ should act in re-enforcing local meaning through the preservation and adoption of symbols of recognition and communication codes within an urban form that retains and reveals various layers of fabric that connect to the past. Use of symbols of community recognition should not however result in a form of segregation to other sub-cultures, or indeed be appropriated entirely so as to be meaningless. Instead, they should be used jointly with new symbols that link to a wider community and higher order cultures.

In order to demonstrate how the utilisation of social links can be successfully used to produce a revitalised ‘intensive’ urban form for the direct benefit of the local community, whilst also helping to form links both within the community, and with local and external governing bodies, the inner city estate of Angell Town, in Brixton, south London provides an ideal case study. Originally built in the 1970’s, the estate was intended to provide social housing for some 4000. However, due to poor linkages, lack of community facilities and homes built from poorly constructed concrete blocks connected by high-level bridges, with garages at ground level, Angell Town quickly become associated with crime, vandalism, social exclusion and all of the attributes of so called ‘sink estates’. It was as a direct result of the formation of the residents based Angell Town Community Project (ATCP) that a socially based force for regeneration developed which not only gained political backing from the local Lambeth Council, but also secured £5m of European Regional Development Funding, and later 67m of Estate Action programme funds in 1998.

The ATCP took particular care to ensure that all members of the community were involved in the drawing up of a Masterplan for the regeneration of the estate. They then worked in close partnership with a specialist group of urban regeneration consultants (indeed employing them through Lambeth Council) to produce a plan intended to represent the needs and desires of the community. What was produced was a series of plans designed to produce an intensive urban form but one which no longer ‘ghettoised’ the estate by utilising traditional scaled built forms and patterns of movement that reflected and thus integrated with the remainder of Brixton. Through a combination of redevelopment and refurbishment, the new estate utilises a built form that unlike much of social housing, does not appear like social housing. The variety of styles and use of materials appears is intended to appear ‘modern’, ‘aspirational’ and ‘forward looking’, specifically fashioned with the intention of creating a positive perception of not only the estate, but also its residents. New businesses have been established within the estate, and self-build schemes have brought new skills to some of the residents. Active frontage has been introduced along with positive public spaces that have been named by the community after events within the history of the estate, in order to celebrate both its past and its commonality. Therefore, the urban form draws on the traditional, links with the past, but also re-invents the space to become a new place. It is designed to meet the everyday needs of the existing community, but also serves as a physical manifestation of their desires to become more than they were, allowing them to re-gain their place in the wider community without sacrificing their own identity. Importantly, it creates a self-controlled and internally revitalised identifiable sense of place that encourages and thrives on movement, interaction and social connections. In brief, an urban renaissance fuelled by the desires of a local community that is both inward and outward looking, and which reasserts the space of place without compromising to space of flows.

In conclusion therefore, it is considered that the drive for ‘intensification’ can be viewed as part of a wider reaction against the perceived erosion in the importance of space by the growing importance of the new ‘space of flows’ that represents the ‘information age’. It represents one part of a wider attempt to re-invent the post-industrial city following the collapse of the UK’s manufacturing base. Interestingly though, it can also be viewed as an attempt to utilise the power of the new virtual links and create a structure much like those used in the exchange of information, a multi-linked conduit that will prove irresistible to the new ‘space of flows’. This therefore suggests that there is a legitimate claim that plan based principles used along side inventive urban design could create an urban form suitable to house the new dynamics of the information age.

Bibliography

Bertalanffy, Ludwig Van (1976) General Systems Theory; Foundations, Development, Applications. New York: George Braziller.

Brand, P (2004) Urban Environmentalism. London: Routledge

Castells, M (1989) The Information City: Information technology, economic restructuring, and the urban-regional process. New York: Blackwell

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (2006) Angell Town,Brixton, London – Case Study. Retrieved on the 23 March 2007 from the World Wide Web. http://www.cabe.org.uk/default.aspx?contentitemid=1616&field=sitesearch&term=angell%20town&type=0

European Union (2005) eEurope – An Information Society for all. Retrieved on the 23 March 2007 from the World Wide Web. http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/eeurope/2005/index_en.htm

Gronlund, B (1999) Rem Koolhaas’ Generic City. Retrieved on 21 March 2007 from the World Wide Web. http://hjem.get2net.dk./gronlund/Koolhaas.html

Habraken, N.J (English Translation 1972) Supports, an alternative to mass housing. London: Architectural Press

Jenks, M. (2002) The Compact City – A sustainable urban form? London: E & F Spon.

O’Bryan, D (1997) Living the Global City – Working Class Culture, Local community and global conditions. London: Routledge

Shane, D.G (2004) Recombinat Urbanism: Conceptual Modelling in Architecture, Urban Design and City Theory. Wiley

Watson, G B & Bentley I (2007) Identity by Design Oxford: Elsevier